URLs are for Web Apps, not Hybrid Apps.

When we started planning to build what soon became Ionic, we knew that we needed to take a native-focused approach to building the next great HTML5 development framework.

We felt that there were plenty of web-focused HTML5 frameworks, but few that treated HTML5 as a first-class citizen in the app store. We couldn’t ignore that people increasingly look to the app store to find apps, rather than browse the web for them.

One big difference that kept coming up between web apps and native apps is how they handle URLs. Web apps utilize URLs both for the developer’s convenience but also for the user’s, allowing people all over the world to link directly to content and using them to delineate parts of a user interface. Native apps, in comparison, don’t use URLs for UI interactions, or use them only under the hood for the developer’s convenience.

In a native app, a user will never see any URLs even if the app is using URL based routing underneath. Obviously there are no URL bars or browser chrome in a native app so having URLs doesn’t make sense. When used, it’s merely a convenient way to manage UI state for the developer.

Yet most current HTML5 development frameworks have kept URLs as a core concept, limiting a lot of UI interaction to those that can triggered through an anchor like <a href="nextPage.html"></a>. Things like switching to a new page, popping up a dialog box, or linking tabs. It’s probably out of developer comfort, but also because the history of HTML5 and web technology is rooted in the browser app. But even then, URLs were meant to link to specific resources on the web, not to control user interface interactions.

If you are familiar with native app development, you’ll know that native apps tend to utilize a lower level design pattern called theView Controller pattern (ignore the Model portion for now). The idea is pretty simple: you have a set of views (think of them as boxes or rectangles where UI elements are drawn), and then controllers that manage multiple views in tandem.

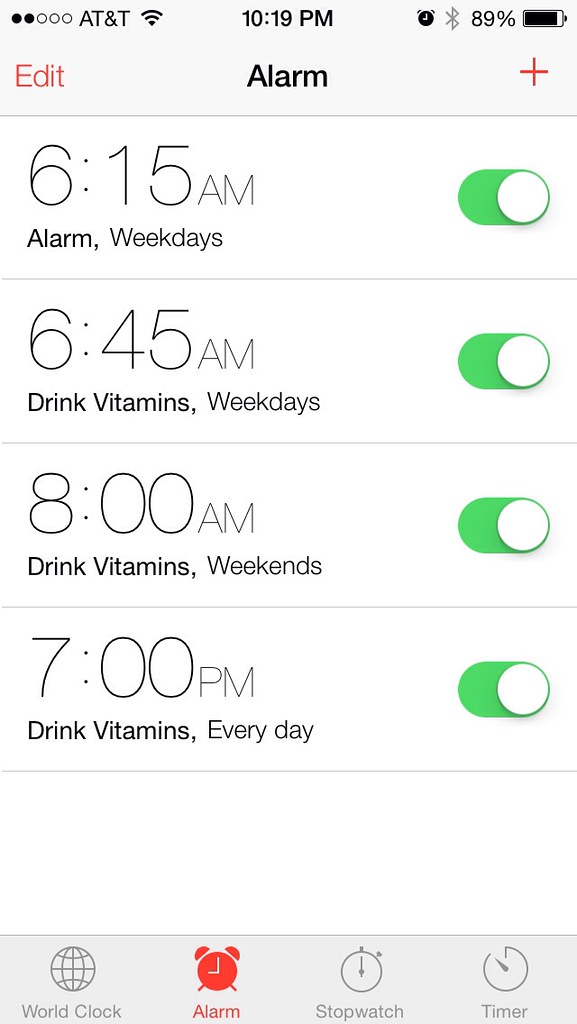

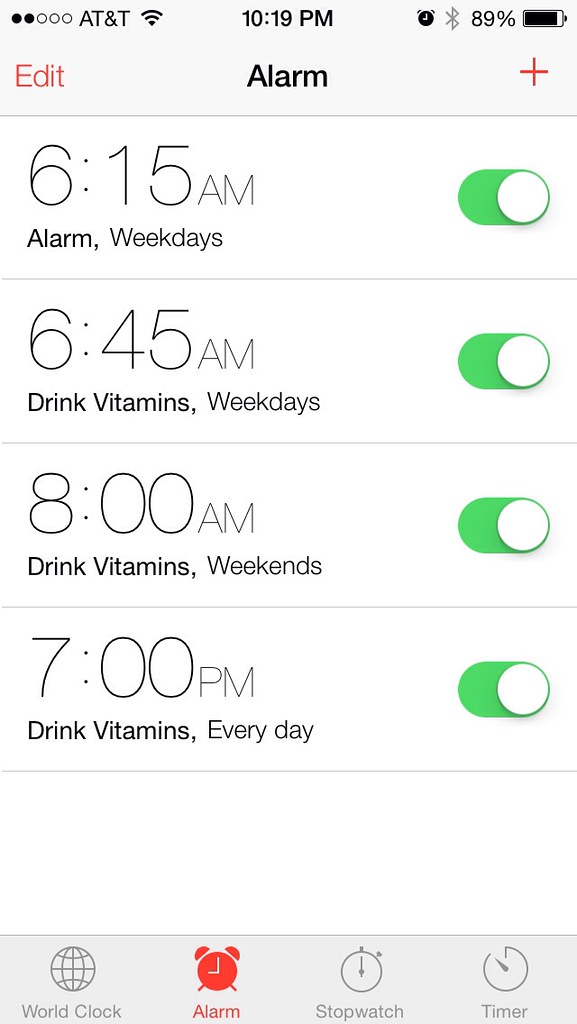

The UITabBarController on iOS is a perfect example of this. It takes a set of child controllers which each have their own set of views that make up each “page” in the tabs, and manages tabbing between them:

In the screenshot of the iOS Alarm app above, you’ll notice four tab buttons with four possible pages of the tab you can select. We are currently on the “Alarm” tab. The UITabBarController holds a reference to the UITabBar view at the bottom (it even creates it for you), and then when a tab is selected, the controller makes sure to switch the pages for you.

In a Web App, you might have a distinct URL for each page in the tab. That wouldn’t be the worst thing in the world for a hybrid/native app, but it soon breaks down when we look at more complicated native apps. For example, the great Yahoo! Weather app:

If you haven’t used the Yahoo Weather app before (highly recommended), it features one single pane that scrolls up displaying a variety of weather information. The user can also swipe in between each city they’ve added, showing weather for that city:

Imagine trying to model this drag animation using a URL-to-City approach in a back or frontend framework that uses route based navigation. Let’s say the first page is /cities/current and the second page is /cities/Madison-WI. When the user starts dragging to the next page, what happens? Do we navigate to /cities/Madison-WI, or do we wait until they complete the drag? If the routing system uses the URL state to know when to render each page, then we are stuck trying to hack around the router.

Instead of being a convenience, URL-based routing becomes an artistic restriction.

Ionic: Native Applied to Web, And Back Again

To native developers, this all might seem like a pedantic exercise, but for web developers moving to native development, it is often quite a change to not use URLs for common UI interactions. We don’t just link to different pages using <a href="page2.html"></a>, we use more subtle tools often powered by touch, letting the user treat our app as an open canvas.

With Ionic, we wanted to apply these native design patterns to web development. And in doing so, we realized something really exciting: HTML5 was just as powerful and flexible as native development. But better still, it had some major benefits over native: it was faster to build in, easier to port across platforms, and known by a lot more developers.

We realized that if we could build an HTML5 framework that loved native design concepts instead of avoiding them, we could enable developers to build any kind of app they dreamed up, not just ones that worked with the URL pattern.

So we decided to apply the View Controller pattern to a lot of the ways developers build UI interactions in Ionic. If you are a web developer that hasn’t had much experience with native development, it will probably feel a bit strange at first. We are confident that once you see what is possible when you free yourself from the URL, you’ll feel quite empowered to build great apps in HTML5.